I’m a therapist—a relatively new therapist as I went back to school for my masters’ in clinical mental health counseling when my kids were teenagers. I had multi-faceted reasons for pursuing a counseling degree, but a big one was my desire to effectively help families on the front end of the teenage years.

- What if there wasn’t a need for so many mental health professionals?

- What if our waitlists weren’t so long?

- What if the church and trained professional counselors rose up to help families more proactively?

- What if parents knew better how to enter in with their kids?

- How can I help with that?

This is my heart.

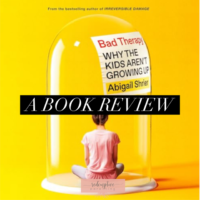

But if you read Bad Therapy, no counselor like me exists. Rather, all counselors usurp parents’ authority, try to keep kids in unending therapy, readily recommend meds, support all teen smartphone use, and elevate feelings as fact. There are counselors like this, which is why I am very deliberate in who I refer to. As with any profession, there are those who are good, ethical, and highly effective, and those who are not.

Where Bad Therapy Went Wrong

With that said, one of my biggest issues with Bad Therapy is the abundance of over-generalizations about all therapists and therapy. We are not all everything said. Furthermore, our culture is in crisis and there is a real need for therapeutic help. Now do I think every problem necessitates counseling? By no means! My hope is to see more parents, churches, and friends rise up and step in, instead of this idea that it always must be the professional.

The over-generalizations caused me to question what else in the book might not be accurate. The author’s assertion against what has become common protocol for trauma-informed help and thinking about the body’s way of storing traumatic memories really caused me to question.

Dismissing evidence-based neuroscience research on how trauma effects our bodies and alters our brains, including Bessel van der Kolk’s book The Body Keeps the Score, the author quotes counter experts. She also debunks the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) initiative, which is used in many settings including foster care and adoption agencies. As a counselor taught these things in my faith-integrated program I found the trauma chapter so unsettling that I spent hours on a research quest. I was confused for one because I had never heard anything contrary, and because even at a biblical counseling conference this past fall a well-respected biblical counselor talked about the importance of taking a holistic approach (body/mind/soul) to healing and understanding trauma survivors’ altered connection with their bodies. I have pages of notes from that seminar that integrated theology and counseling, and I specifically remember feeling grateful to hear a biblical counselor say similar things to what I’ve read and learned from secular sources.

But if I was not a therapist (as most reading the book aren’t), I would assume everything written in the book about trauma and healing is right, and all the bad neuroscientists and therapists have it wrong. It’s just not that black or white.

What Bad Therapy Got Right

But before dismissing Bad Therapy as all bad and not worth your read, there are many parts of the book I whole-heartedly agree with. It too is not that black or white.

The author states that according to the American Counseling Association (ACA), counselors come into therapy as a “blank slate” and don’t impose their own values. Ethically I am not to share my beliefs; but none of us are a blank slate. We all have our biases and worldview, which means as a believer how I approach therapy is very different from someone who holds to a different worldview. My approach will vary even from another Christian counselor. Therefore, who we seek out counseling from matters!

Recognizing the influence I have on an adolescent in my care is important. A young person may very well respond to a question with an answer she thinks I want to hear or reflects well on her. The author discusses this power imbalance as it relates to the wording of mental health questionnaires and interviewing by school and medical professionals or therapists, and I agree with the author that some of our classroom initiatives, school district and government required check-ins, and mental health diagnostic forms need revamping.

Like the author, I too am an advocate for therapy for parents as the way to help kids. Take anxiety for example, parents often transmit their anxiety on to their kids. Whether this is the case or not, evidence shows parent-based approaches to be effective. By nature of parents doing therapeutic work, they learn how to help their own children. I love this.

Many of the other critiques in the book that I agree with appear targeted at parenting and culture today—not therapists. For instance, the author speaks to the ways we try to order a perfect world of perpetual happiness for our kids:

“Hang around families with young children for an afternoon, and you’ll hear parents check that their kids are enjoying their ice cream, excited about school the next day, that they had fun at the park. In so many ways we signal to kids: your happiness is the ultimate goal; it’s what we’re all livin’ for (p. 49).”

Also, the ways we are inhibiting the development of flexibility and adaption:

“Banishing normal chaos from a child’s world is precisely the opposite of what you would do if you wanted to produce an adult capable of enjoying life’s intrinsic bittersweetness.” We’re making our kids less tolerant of the world (p. 52).”

As well as agency:

“They’re (young people) afraid not to be amazing… compared with young people a decade ago they have no agency… They’ve been trained to seek approval from others before making decisions and taking risk (p. 62-63).”

And our failure to assert our authority:

“This generation of kids is absolutely not afraid of their parents… In large part this is because parents have avoided appealing to their own authority…We seem to be working so hard to be nonjudgmental and understand a child’s frustration that we cater to their feelings instead of teaching our child to learn to control his impulses… (p. 170).”

Why I Hope You’ll Read

My first inclination was to steer parents away from this book because of the unjust lump assumptions about therapists, even when there are therapists who fit the descriptions. Additionally, like my qualms with TikTok mental health accounts that have misled many to self-diagnosis, I hate that valid trauma informed help will now be viewed as suspect. But reading this book I hope challenges parents to see where we should and could do more to prevent and/or help our own children. Maybe therapists won’t be so widely needed. Or, how we are needed will be different—more on the front end alongside parents.

This is my heart.